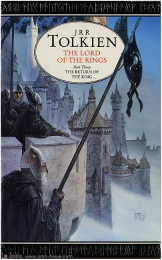

This week in the Lord of the Rings re-read, we consider “The Field of Cormallen,” Chapter 4 of book VI of The Return of the King. Spoilers for the entire book after the jump.

What Happens

The armies of the West are being defeated when the Eagles arrive. Shortly after, they all see the Black Gate crumble and a vast shadow rise and dissipate in the wind. Gandalf announces that Frodo has fulfilled his quest and asks the Eagles to bring him to Mount Doom. There, they rescue Frodo and Sam from a small hill, which Sam had convinced Frodo to move to.

Sam wakes in Ithilien two weeks later, finding to his surprise and delight Gandalf (alive) and Frodo (still missing a finger but healed). They are brought to a great field where Aragorn greets them and places them on a throne, and listen to a minstrel sing of Frodo of the Nine Fingers and the Ring of Doom. At the subsequent feast, they are reunited with the remaining members of the Fellowship. Among other stories, Gimli tells of finding Pippin under a heap of bodies. About three weeks later, they return to Minas Tirith and wait for the morning, when Aragorn will enter the city.

Comments

Somehow I’d forgotten that the rescue of Frodo and Sam happens so soon, page-wise, after the Ring’s destruction. I think I got this chapter mixed up with the next, when we go back in the timeline to see Faramir and Éowyn.

(As for the logistics of the rescue, we talked at length about why not use the Eagles earlier way back during “The Council of Elrond,” which I recommend if you’re new here, or just to refresh your memory; but please do feel free to add your own thoughts.)

Another interesting thing about the rescue is that, though last chapter we left Frodo with peace in his eyes, this chapter he has clearly not been reset to his pre-quest state. When Sam says he doesn’t want to give up yet, Frodo responds:

Maybe not, Sam, but it’s like things are in the world. Hopes fail. An end comes. We have only a little time to wait now. We are lost in ruin and downfall, and there is no escape.

Which, uh, that’s “trapped in a post-apocalyptic world” talk, not “we just vaporized the single biggest active source of evil in our world” talk. Or, as we discussed last time, “affected by serious psychological issues” talk. At any rate, it’s a very small part of this chapter, which is generally very non-depressing, but it’s worth noting as setup for the rest of the book.

* * *

Before we move away from the start of the chapter, there are a couple of things I wanted to mention about the scene before the Black Gate that opens the chapter. First, Aragorn and Gandalf are depicted as silent and still during the fighting, visible under banner and on hilltop, respectively, not in the thick of the fighting. It’s entirely sensible for them to be acting as generals and visible-sources-of-hope, and yet not what I am conditioned to expect from fantasy novels, which probably says nothing good about genre conventions.

Then, of course, there’s the Eagles, whose coming echoes back to The Hobbit in a way that shouldn’t be intrusive to those who haven’t read that book. It’s the same phrase, of course, but that’s not flagged in the text, and the Eagles aren’t critical to winning the battle, just to rescuing Frodo and Sam after it’s all over. Still, I think it’s a nice little resonance.

A more explicit resonance is yet more wave imagery, this time in Sauron’s shadow-shape “rear(ing) above the world” and “lean(ing) over them” before dissolving. This image will also return at Saruman’s death, several chapters from now.

Finally for the battle, there are some interesting bits about the nature of those fighting for Sauron. All of them are directly influenced by Sauron’s will, which “fill(s) them with hate and fury,” and when that will is removed, they feel fear. But the species react differently when Sauron is destroyed. Those who are his “creatures,” whether “orc or troll or beast spell-enslaved,” become “mindless” and lose all interest in the battle, killing themselves or fleeing to hide. Which I wouldn’t have expected from the way the Orcs we’ve previously met behaved; they seemed to have more individual personality than is consistent with being so heavily dependent on Sauron for their motivations. In contrast, the humans choose whether to continue fighting in their hatred and pride, or to flee, or to surrender. This suggests to me that the non-humans do not have the ability to choose between good and evil, or, interestingly, even the ability to continue in evil after Sauron’s destruction, as none of them continue to fight. (From what I can recall, there’s no explicit mention of fighting non-humans from now on. The end of this chapter talks about fighting Easterlings and Southrons, and the mention of Éomer riding to war beside Aragorn in Appendix A speaks only of “many enemies” and riding “beyond the Sea of Rhûn and on the far fields of the South.”) And that may be a logical extension of the idea that the non-humans under Sauron’s sway don’t have full free will, but it’s still rather unusual.

* * *

The section where the minstrel sings Frodo and Sam’s story. This is another “wow, I am so not the audience for this” moment, because I cannot imagine myself as Sam or, particularly, Frodo, sitting and listening to that. I mean, the last time I left a job, I could barely stand the very brief “thanks, you’ve been great” speech at my leaving party. At least an hour’s worth of a minstrel singing my praises, while sitting on a frickin’ throne (wearing tattered Orc-rags, better still) in front of everyone? I think the sheer weight of my embarrassment would cause me to just slide off the throne and sink right into the earth.

I can envision that Sam has a different reaction, but Frodo? He doesn’t say anything despair-ridden after waking up, but I can’t imagine that he could listen to the tale of his anguish and failures without some serious emotional distress, even in the context of everyone praising him.

I do like the description of literary catharsis as having one’s heart “wounded with sweet words,” so that “pain and delight flow together and tears are the very wine of blessedness,” however. That I certainly recognize, the desire to read or listen to something that will make me cry, but in a good way.

* * *

It’s nice to see the Fellowship reunited at the feast after. Pippin made me smile when he told Sam and Frodo, “We are knights of the City and of the Mark, as I hope you observe.” I note that Gandalf insists Frodo wear a sword to dinner—is this only a matter of what’s proper formal dress, to go with the “circlets of silver upon their heads”?

Some other miscellany:

Merry and Pippin have grown three inches, which is significant indeed when the tallest hobbit previously was only 4′ 5″.

Gimli helpfully tells us how Pippin lived, though in an unfortunately clunky passage; I think it would been less obviously an expository lump if someone else had said it, or if it had been spread across dialogue rather than in a monologue.

Even this reunion has in it the seeds of separation, as Legolas leaves singing of the Sea and how “I will leave, I will leave the woods that bore me.” I don’t think there’s a way for the reader to extend this idea to Frodo yet, but if there’s such a thing as retroactive foreshadowing, I think this would qualify.

* * *

They spend about three weeks there before returning to Minas Tirith to see “again the white towers under tall Mindolluin, the City of the Men of Gondor, last memory of Westernesse, that had passed through the darkness and fire to a new day” (isn’t that gorgeous?). This feels weirdly leisurely, even if the explanation in the text is sensible, and I think it’s because we don’t know yet what’s been happening in Minas Tirith in the interim. Which, happily, is what we’ll get next chapter.

* * *

And now, some silliness. Note: earworm warning, children’s song version.

SteelyKid is just over two years old now and, as toddlers do, likes us to sing “The Wheels on the Bus”—which she requests as “round and round,” since the first and last verses are, for the unfamiliar,

The wheels on the bus go round and round, round and round, round and round,

The wheels on the bus go round and round,

All through the town.

The standard verses involves things and passengers on the bus (some of which presume a public transit model, though I personally prefer a school bus model since that will be more immediately relevant to SteelyKid). Chad, however, likes to make up new verses; you can find some of them, mostly physics jokes, at his blog.

One day as he was telling me a new one, I found myself starting to make up Tolkien verses, and then we were both off and running. Here’s what we’ve got so far; the first five are mine (well, Chad polished the last one), and the rest are his.

- The hobbits on the bus eat six meals, eat six meals, eat six meals;

- Gollum on the bus says “My precious,” “My precious,” “My precious”;

- The dwarves on the bus delved too deep, delved too deep, delved too deep;

- The Nazgûl on the bus have nine Rings, have nine Rings, have nine Rings;

- Gandalf’s on the bus, you shall not pass, shall not pass, shall not pass;

- The Balrog on the bus is smoke and flame, smoke and flame, smoke and flame;

- Gandalf as he falls cries “Fly you fools,” “Fly you fools,” “Fly you fools”;

- The Trolls on the bus all turned to stone, turned to stone, turned to stone;

- The Strider on the bus is still not King, still not King, still not King;

-

The Narsil on the bus has been re-forged, been re-forged, been re-forged;

and, finally,

- The Rohirrim prefer to ride a horse, ride a horse, ride a horse.

(Bonus movie verse: The Orcs on the bus have a cave troll, a cave troll, a cave troll.)

Yes, this is what life is like here in Chateau Steelypips.

Contributions? Revisions? Requests to go away and never speak to you all again?

« Return of the King VI.3 | Index<!– | Return of the King VI.4 »–>

Kate Nepveu was born in South Korea and grew up in New England. She now lives in upstate New York where she is practicing law, raising a family, and (in her copious free time) writing at her LiveJournal and booklog.

Two more, one that we came up with before and I forgot, and one I came up with this morning:

* The Ents on the bus say “Hoom, hoom, hoom,” ”Hoom, hoom, hoom,” “Hoom, hoom, hoom.”

* Tolkien on the bus just keeps revising, keeps revising, keeps revising.

I’m going away now, really.

Actually, the connection between the Eagles and The Hobbit is flagged in the text. It’s just that it gets flagged at the end of Book V. As the troll falls on him and he hears people shouting about the eagles, Pippin’s last thought is something like, “No, wait. That was Bilbo’s story, not mine.”

While waiting for the end, Sam gets very meta again, talking about being in a story and all. It’s interesting that the title he gives the tale is exactly the same one the bard uses later. I suspect Frodo had a hand in that.

Like you, I find being in the position that Sam and Frodo are in during the ceremonial bits utterly cringe-worthy. I think I’d be wishing the eagles had come just a little too late. That said, for the first time I see C.S. Lewis cribbing from his pal Tolkien again. The scene at the end of TLtWatW where the Pevensey children a crowned and enthroned is very reminiscent of this scene.

I think the reason the orcs and the evil creatures all run for the hills while the men keep fighting is that they are creatures of darkness. It has been emphasized several times that it is unusual for orcs and trolls and whatnot to be abroad by daylight. It is implied that this is a sign of Sauron’s growing power. Now that that power has been destroyed, they are no longer sustained against the sun and flee back to their tunnels and caverns.

This is another one of those “restful” chapters where not much happens other than a bit of talk. Tolkien seems to be fond of them right after some major action. What’s odd is that the next 3 chapters are very similar. It’s very realistic, but an odd choice in a literary construct.

Thanks Kate, I will be singing that song to myself for the rest of the day.

how about:

The eagles on the bus save the day, save the day, save the day.

when I first read it was a relief when the eagles arrived just at the right time to save Frodo and Sam, This time it seem a bit too convenient, (like the orcs forcing the across Mordor) but I can’t think of a better way they could have been reintroduced.

It seems reasonable that the orcs morale would be broken when the Sauron is destroyed, they don’t have much discipline at the best of times and need a bigger bully than them selves to keep them under control.

The Orcs on the bus fight at the back, fight at the back, fight at the back, all day long (or until they are kicked off by the driver and have to walk home)

I don’t understand why more people don’t grok that giving the Ring to Gwaihir, or any Eagle, is exactly as dumb as it has been established that giving it to Gandalf or Galadriel, or even Aragorn or Boromir, would be. Is it that they think they’re just useful tools for picking things up with?

If Jackson has to do his Hobbit project, I hope he will at least take the opportunity to educate the movie-going public about that. Eagles aren’t forks!

Best earworm *ever*. Thank you.

I didn’t like thia chapter much. I felt that Frodo was being pushed around too much. Wearing the hated Orc-rags? bleh. Having to wear a sword at dinner? blah. Sitting through a song that just sounds meant to remind you about the finger you lost? blargh.

Maybe it is intended for the audience army, but it feels too much like Frodo was pushed into it.

The movie of the books changed too many things, too many things, too many things…

Tom Bombadil mounts an eagle. Flies to Mt. Doom. Drops in ring.

Doesn’t have the same scale or scope or drama… but one wonders why, what with the cosmological stakes involved, it didn’t happen just that way. Wasn’t Tom on the order of Valar?

Even if you could persuade Bombadil to do it, he’d only get distracted half way across the Misty Mountains and drop the ring, starting the whole wretched business all over again.

DemetriosX @@@@@ #2, thanks for the reminder. And the bit about the title of the lay reminds me that Chad had mentioned where the minstrel got his information; I had assumed that Gandalf had read it from Frodo and Sam’s minds, as he did in Rivendell, since otherwise it would be a massively quick composition; but the title would certainly be within the timeframe given. And good point about the darkness, though that doesn’t answer why they don’t continue to fight or harass later, during the nights.

mark-p @@@@@ #3, I love the Orcs verse.

del @@@@@ #4, “Eagles aren’t forks” is a lovely mantra.

Owldaughter @@@@@ #5, I’m glad you liked it.

sps49 @@@@@ #6, it’s very weird, isn’t it, since it was clearly _meant_ to be a vast reward and there’s nothing in the text to suggest that Frodo took it any differently, but even given my embarrassment issues I still have a hard time believing that Frodo would react that way. And I like your verse, too.

Lemnoc @@@@@ #7, oh boy, Bombadil. We did a pretty extensive hash-out of theories of his nature back in I.7, and I personally do not subscribe to the theory that he was a Valar or on the order of them. All I can say otherwise is that Tolkien created him with such a character, as described by Gandalf, that he would be vastly unsuited to the task.

(Or, on preview, what Iain_Coleman @@@@@ #8 said.)

Someone alluded to it in comments for the last chapter, and i’m now really curious about the amputation theme: nine-fingered Frodo, Beren One-hand, and the others. Anyone have insight on this? Is there something about sacrificing the hand in particular that’s significant for Tolkein specifically, or to do with Catholicism or Christianity?

I suspect many of us [myself included] would not deal easily with adulation; however happily-ever-after always begins with a crowning, or kissing the girl in front of the cheering crowd, or holding up and waving the trophy. Part of the expected plot and it doesn’t bother me.

Frodo may have resumed his own inner-peace but that does not mean that he has forgotten any lessons he may have learned about the meaning of life, or about the fact that he is a bright boy and sees that they are on a hill that is about to be engulfed by lava with no hope of escape. He’s bright enough to anticipate that This Is The End because he doesn’t anticipate a rescue and I wonder if anyone who knows more about Christianity than me could make anything out of an unexpected rescue from death on wings of eagles [there are various references in Isaiah and other prophets to being ‘lifted on wings of eagles’ from the jaws of death but JRRT was not writing from the Jewish perspective]. This part does not bother me; I think Frodo’s acceptance of his apparently obvious and inevitable fate rather than railing against it speaks volumes about his return from the influence of the Ring.

Many a role-playing gamer had the Eagles flying over Mt. Doom and yelling “bombs away!” however it generally meant a short game. I suppose Elrond and Gandalf could have arranged it but we would have had an awful lot of blank pages in Books II-VI…

I have a few ear-worms for you including:

The Sons of Feanor were gnarly dudes…

The Balrogs on the bus unveiled their wings…

The dragon on the bus could not squeeze in…

The Smeagol on the bus paid double fare…

Speaking of which, Frodo acknowledged Smeagol’s contribution without which everything would have failed. But did Gollum get his own song? Rank discrimination!

May I propose:

Smeagol of the Eleven Fingers and the Banana Peel of Doom

[sorry that I can’t let go of it…]

The wave imagry might also echo the destruction of Numenor.

Nancy@12

Also the revenge of Ulmo and/or the Teleri?

Wow, Kate, and some other readers! My reaction to this chapter was so different and probably what JRRT hoped readers would feel–just the pure joy of the victory of good. I know it gets more complex later on with the decline of the Elves, and the extinction of Ents, and the failure of so much of the beauty of Middle Earth, and most of all Frodo’s pain. But for now there’s unabased rejoicing! So I am going to enjoy this party.

Was kinda teasing about “Bombs Away” Bombadil, but I actually never got the sense he couldn’t complete a mission or take 20 minutes out of his day for a quick joyride to the Black Lands. What Gandalf said was if you just left the ring in Tom’s keeping he’d probably just lose track of it eventually. Not incapable. Just careless–after all, the thing has no merit or meaning to him.

But… I agree that would leave a lot of pages with nothing other than strawberries and cream and merrymaking…

“Here, at the end of all things,” perhaps we can have a discussion about some of the more perplexing/frustrating of items about LOTR.

The leading quote above was–to me–one of the most moving passages in the whole cycle, the realization of Frodo that they’d indeed given their all, their lives, for their moment of Doom. Days before, I think, Frodo had realized what Samwise had not, that this was a journey from which they would never return. Yet he pressed on.

The fact that both did survive, and relatively unscathed was, from the standpoint of dramatic fiction and mythopoeic sacrifice, a weakness of LOTR. This outcome was, after all, no Beowulf; this was, in essence, a hedge between the epic mythopoeic storytelling we all recognize LOTR aspired to and the “there and back again” ethos of The Hobbit that so charmed us children ’round the hearth and under quilts, so to speak. Happy ending, uber alles.

Someone needed to commit the transcendent “ultimate sacrifice” in LOTR, and it had to be someone other than Gollum. But, in the end, it was only Gollum. I think Tolkien the scholar understood this inherent weakness, which is why he designed that Frodo never, ever really recovered from his adventure.

Reason I bring this up is the obvious deux ex machina of the Eagles, which so many have made fun of over the decades, including myself in an earlier thread.

Now that we’re “at the end of all things,” I may cover the deux ex machina in a different thread, but let me say here that had JRR committed his Hobbits to the ultimate sacrifice, to the bold, heartwrenching sacrifice whispered of reverently by later kings and wizards, of deprivation and forelorn death of those most kindly and noble of creatures, irrecoverable on a distant lonely mountain as the sun rose brightly on a New Age, a sacrifice for which all men should kneel and give thanks…

…well, our perhaps mythopoeic cycle wouldn’t need rescue by Eagles….

Lemnoc@16,

Do you think the sparing of Frodo and Sam could be an act of grace, which I understand is an integral part of the Catholic theology? Frodo [and Sam] indeed have to leave the world, but not in a fried fashion on the lava-hill. I don’t find the survival of our two heros troubling; I find it quite fitting in the world JRRT designed, where the Valar can have mercy on Galadrial after ~7000 years, and can even give Smeagol some meaning to his existence [not that he was in any position to appreciate it].

Whether the Eagles are any more deux-ex-machina than Gandalf showing up in Fangorn is another discussion; at least unlike traditional deux moments that are completely inexplicable and do not arise from the plot—the Eagles were already there, Gandalf had already ridden an Eagle, and we might have seen this coming [since when is Sauron the only one who gets an Air Force?]

I don’t find these issues troubling because I don’t feel obliged to make Middle-Earth fit into the exact same pattern as other mythological worlds. JRRT did the unexpected; he did it in a way that I suspect fit with his feelings about unexpected salvation [or as CS Lewis would put it, Surprised by Grace—insert Will and Jack joke at your peril].

Dr. Thanatos @16, Yes, I do think the sparing of our heroes was an act of Grace. I am not troubled by it, except perhaps (and even then, not really) through the conventions that arose to prevent their sad demise.

Here at the end of all things, perhaps a discussion of deux ex machina.

* Of those, the Eagles are perhaps the most prominent example?

* I’d also add almost everything having to do with the palantír, which lets characters know a whole lot more about the world and their situation than they would otherwise.

Any others?

* Tom Bombadil is maybe the most exasperating example of the unused deux ex machina, a device that could have allowed all conflict to be resolved… introduced but unused. Wondrous. Puzzling.

* The Dead are kind of a deux ex machina, only their purpose seems primarily to unwind another deus ex machina, the corsairs. The latter seem introduced to scale up and make impossible the threat to the Battle of Pelennor Fields, the overwhelming threat of Sauron and his minions, then neutralized by the Dead.

I think the Peter Jackson film dealt with this handily: One CGI special effect threat overwhelmed by another CGI special effect threat. The threat of the corsairs, which I never really “got” as a reader, was neutralized by Aragorn showing up with an Undead army, which I also never really “got.” But it did spare Aragorn from being target practice when the Witch-King showed up on the battlefield… which is perhaps Tolkein’s ulimtate “purpose” for Aragorn’s side trip?? Witch-King eats of the fodder of lesser kings?

I cry during the National Anthem (I’m American) – especially when it is played at baseball games or at the medal ceremonies for major sporting events (read Olympics, but not exclusively). It is my pride for the triumph they are experiencing from victory on the field of battle (or just baseball).

I’m with Pilgrimsoul @14 – There is a time for celebration and adulation. And this is it for this story. From the time Sam opens his eyes to Legolas lamenting “to the sea,” the emotional fireworks are in full force. And this reading, like in my previous 13 readings, the emotions are only stronger. Is it corney? A little, but the emotions are played well. And I love it. It is the triumph, the glory and “pure joy” of the moment.

I cried at the Medal Ceremony during Star Wars – A New Hope.

I cried when Sidney Carton walked to the guillotine and his “far far better rest”

I cried at the playing of “An America Symphony” during the movie Mr Hollands Opus.

I did not cry when Amberle turned into a tree in the Elfstone of Shannara – but could have

I cry at the beginning of the Movie Scrooge (the Musical with Albert Finney) remembering the ending.

And I cry every time I read this chapter.

Not to make this a personal post, but worth stating because this is the emotional zenith of the book. Everything else is conclusion.

The Wood Elves on the bus make merry all night. Merry all night, Merry all night.

Lemnoc @16:

Days before, I think, Frodo had realized what Samwise had not, that this was a journey from which they would never return. Yet he pressed on.

IIRC Sam had also come to the same realisation in the last chapter; he too pressed on. I thought their responses post the ring’s destruction were telling: Sam still expressed Hobbit-like optimism while Frodo just wanted it to end (the ring had been such a damaging burden).

“I may cover the deux ex machina in a different thread”

Deus ex aquilae?

Overall, a happy chapter but with bitter-sweet moments. Frodo & Sam would have found being feted embarrassing but in a sense, it was not about what they (might have) wanted. They were part of the excuse to celebrate, and however cringe-worthy they might have found the experience, they did send the One Ring to its destruction; a major feat that needed to be acknowledged by those who have lived in the Shadow of Mordor for such a long time.

The oliphant on the bus is grey as a mouse, grey as a mouse, grey as a mouse…

And now for something completely different: London Underground, the Middle Earth version.

sps49 @6, and others: I think Tolkien found these scenes cringe-worthy also; at least, a part of him did, and that part knew that Frodo (mostly) hated it.

But it is the sort of ritual the societies he depicts would insist upon and so it makes sense. And, as you also said, it was “intended for the audience army” and for us, as well. We can cringe, or cheer, as our experience and character demand.

More generally, I suspect Tolkien intended the adulation as a kind of irony, given Frodo’s ultimate, unworldly, fate. Frodo is the last person who needs (or wants) a parade.

Regardless, I am one of those who finds this chapter heartbreaking, in large part because Frodo failed in his task and yet only he (and Sam, who will never tell) knows it. The people of Gondor want a hero and they were going to have one, whether or not Frodo tried to tell them that, well, he’d actually decided to keep the Ring, but that god damned Gollum went and gnawed off his finger …

No, far better to accept the laurels in silence …

Hell, I’m trying to be funny, but I keep tearing up.

To me, this chapter is second only to the final one in its power, and all because of what isn’t said. Just as Sam breaks my heart when he reports on his own by saying only, “Well, I’m back,” so Frodo’s silence in the face of a wave he couldn’t possibly counter breaks it as well.

Or something like that. This chapter is all about last memories, passing through darkness to a new day. Not quite birth and death, but growth and change and all the pain the latter two facts of life bring.

I fear I’m not making any sense, so I’ll stop.

alfoss1540 @19: I didn’t cry at the Medal Ceremony during Star Wars, but I think I understand why you did. And I’ve often thought that Lucas at this chapter in mind when he shot it.

ed-rex @22:

I have a different reading: Frodo succeeded in his task. Though he did not throw the ring into the Cracks of Doom himself, he (and Sam) got it to where it could be destroyed, a non-trivial feat. And ultimately, the ring was destroyed. The heartbreaking part was that the experience damaged him so much that he would never find peace on Middle Earth.

It also goes to the idea that no one person is able to do it all: Frodo had Sam, the rest of the Fellowship mostly held together and weren’t alone even when they split up (Merry & Pippin, Legolas & Gimli). In a way, LotR emphasizes teamwork over individual efforts.

P.S. My other comment in in moderation limbo.

Someone alluded to it in comments for the last chapter, and i’m nowreally curious about the amputation theme: nine-fingered Frodo, BerenOne-hand, and the others. Anyone have insight on this? Is theresomething about sacrificing the hand in particular that’s significant for Tolkein specifically, or to do with Catholicism or Christianity?

I’m unaware of anything in Catholicism that goes in for amputation of the hand. There’s one line in the New Testament, wtte “if thine hand offend thee, cut it off…” but that’s it. And it’s not like any of those characters amputations were self-inflicted wounds.

Maybe he saw a lot of hands or fingers shot off in WWI?

And as a writer he would be dependent on his hands.

Or… Beren was holding the Jewel, the others were all Rings – things of Power, noted for their effect on people. People who see the items WANT them. Maybe it’s related to that wanting, that clinging desire for the things.

Ok, Beren was holding the Silmaril out to drive away Cacharoth…which doesn’t exactly fit, but the rest fits better.

>[there are various references in Isaiah and other prophets to being’lifted on wings of eagles’ from the jaws of death but JRRT was not writing from the Jewish perspective]

The Christians read those prophets too, you know. And Tolkien would remember that Middle-earth is in Old Testament times.

I, too, have some trouble taking the lay of Frodo of the Nine Fingers seriously, but I think that’s a failure, perhaps, in us and our society rather than in Tolkien’s writing. Praise is, indeed, the appropriate counterpart to heroic deeds in the heroic age, and I think that Sam and Frodo are able to appreciate it. We’re not comfortable with pure praise; we’re too inclined to see the dark side, and the wholesale ladling of honor and respect on people who don’t deserve it, or deserve less of it; we know that too often even heroic valor is misapplied for other purposes… and in short, we don’t give praise because we don’t really believe in courage or in glory.

We know too much about the price, and I think Frodo does as well (and the real master-stroke was showing Frodo’s depression afterwords… some soldiers come home from war, and they’ve won, and nothing is the same ever quite again). Tolkien would have been very familiar with that after 1918, and again after 1945.

“Churchill of the Nine Ministries and the Ring of Fate”, anyone?

Maedhros also lost a hand (cut off by a friend and kinsman in order to free him).

I don’t think Frodo enjoyed the praise for himself though I think he had some joy in that Sam was praised and later Aragorn was crowned king and married. Note that either Sam or Frodo did write down what happened since the LOTR is suppose to be derived from their writings; people learned at some point what actually happened and probably at the Field of Cormallen (though bits like the role of Boromir seem to have been made public much later).

I think of it more as another example of the lessening the further we progress from the First Age.

First Age -> Third Age:

Three Silmarils -> One Silmaril (Earendil’s Star whose light was captured in Galadriel’s Phial)

Beren loses hand -> Frodo loses finger

Morgoth the Great Enemy -> Sauron (minion of Morgoth) the Great Enemy

And so on…

Presumably, in the Chronicles of the Fourth Age, evil will once again arise, be defeated by a hero(ine) of the age but at the cost of a chipped nail?

I’m surprised nobody has brought up the term “eucatastrophe” yet.

Apparently it was Tolkein’s own neologism, coined precisely to cover the events of the last chapter and this one. It’s escaped to take on a modest life of its own as a theologica and literary term of art — 10,000 hits on google, and it’s in the more complete dictionaries.

Doug M.

Tim Powers — another fantasy author who’s a devout and practicing Catholic — regularly had his heroes (1) mutilated by the loss of an eye or a finger or such, and (2) bereaved by the loss of a loved one. He’s written in interviews that this is related to the nature of evil; presumably it’s that evil is inherently subtractive, making the world less than it was.

The end of the Third Age is comes in victory, but also with heavy loss. Elves, goodbye. Ents, extinct. Wizards, dead or failed or departed. Lothlorien and Rivendell, just some woods and a valley. As noted in an earlier entry, it’s a declining-magic world, where the defeat of Sauron carries a terrible, heavy price. So it’s entirely appropriate that Frodo should suffer a tangible, physical loss to parallel this.

But why his ring finger instead of an eye or something? I imagine it symbolizes how deeply the Ring had its hooks into him. It had, in a sense, grown into him, so that it was no longer possible for them to be parted without amputation.

Doug M.

Beren’s story has a parallel in Tyr and Fenrir.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C3%BDr

@29 i’m pretty sure that happened to Buffy at some point

And amputation in Norse myth, of course, starts with Odin sacrificing an eye for the secret of the runes.

Frodo wearing a sword to the feast I took as recognition that he had played a role in the war. This is a world where even the kingdom of Gondor has slipped from regarding the military as just a necessary feature to something approaching adulation – remember Boromir and Faramir? Faramir’s words?

So to give Frodo the necessary credit, he must needs wear a sword, though his heart’s not in it.

tonyz@26,

I didn’t read Frodo’s afterstory as depression so much as lingering Ringoholism although the “anniversary syndrome” episodes do make me think of shell-shock [PTSD to you young folk] which JRRT would have been very familiar with. And I didn’t mean to imply that non-Jews did not read Isaiah and the other “old testament” prophets; but they tend to read them very differently than we do.

And what about “Shoeless Joe of the 9 Black Sox players and the World Series of Doom?”

Gonzales@33,

Does that mean the Fellowship were leading the Scooby life?

On the mutilations, perhaps this is more a reflection of Tolkien’s war experience than of his faith. A lot of men came back from the war mutilated in one way or another (physically and psychologically, but the latter is better discussed later). Amputations, scarred lungs, horrible burns.

The deus ex machina (by all means, lets discuss it, but can we please spell it right!) might also have more to do with the war than with religion. A lot of men in the trenches grew resigned to the fact that sooner or later, their number would be up. Whether a stray bullet, a bombardment, or just another suicidal push over the top, they were “at the end of all things”. But then suddenly there was an armistice and they all got plucked out of France and sent home.

Emma Pease @27: I think Merry and Pippin also contributed to the Red Book, so one of them could have added the account of the celebration, much to the embarassment of Sam and Frodo.

Lots of interesting things to respond to.

@@@@@ Doug M 30 I remembered JRRT’s word after I commented. The rescue of Frodo and Sam and the celebration of the “miraculous” victory is a perfect example of Eucatastrophe–“a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world as poignant as grief.”

@@@@@Alfoss1540 Clears throat, wipes eyes. You aren’t the only one. Maybe we should form a Saps Club.

@@@@@Tonyz 26 I understand your point of view, but from JRRT’s knowledge of the heroic tradition having the bard appear to sing the tale and lavish praises is the appropriate thing.

@@@@@ed-rex 22 Frodo did not conceal his failure at Mount Doom. I don’t think the book shows him confessing, but in JRRT’s letters and other writings he mentions that he admitted what happened and felt a failure.

@@@@@Various Despite the well-documented mythopeic tradition, I can’t work up any enthusiasm for snipped off body parts. Sorry.

Frodo did not conceal his failure at Mount Doom.

I must agree. Everyone who got close could see he’d lost a finger. He’d been carrying a finger ring. People can connect the dots. I bet the bard at Cormallen told the whole story.

Responding to someone upthread who thought it made the whole lesser to have Frodo survive instead of dying – I disagree. That would have been the easy way. To have him survive, willing to pay the ultimate price, triumphant, and then realize he’s wounded and will never really heal, is one of the elements that makes it a lasting work.

Another bit of plausibility which may have come from WWI: Frodo’s wound from the fight with the Nazgul is a minor incident relative to the story, but the damage from it doesn’t go away.

Elaine @39,

I agree. Which is a more emotionally resonating ending: good guy gives his all and throws himself on the grenade to save the world, or good guy gives his all, throws himself on the grenade, is miraculously saved, but realizes that there’s no happy ending for him? I think JRRT went beyond the expectations of fantasy [either hero lives happily ever after or dies so everyone else can live happily ever after]—this was something new and I think it worked well…

Wasn’t Tolkien missing a finger himself? In the 2nd Edition foreward he writes about revising the manuscript, “And it had to be typed, and re-typed: by me; the cost of professional typing by the ten-fingered was beyond my means.” I’ve always thought that was part of his personal connection to Frodo.

In the tale of Beren One-Hand there are echoes of Celtic mythology (Nuada Silverhand in the Irish tales).

debra@42,

I took that to mean the cost of hiring a typist with ten fingers [and therefore capable of actually typing], rather than an implication that he himself had lost a finger…

I would take ‘ten-fingered’ here to mean ‘capable of typing with ten fingers’ (as opposed to, say, two, which I suspect is how Tolkien typed).

Silly me! All these years I’ve thought JRRT was missing a finger…too literal a mind.

SoonLee @24:

My reading of Frodo’s “failure” is that the task succeeded, but Frodo failed. But my reading of that failure is very much in line with (I think it was) Michael Swanwick’s contention that Frodo was “tested to destruction” – ie, *no* one in Middle Earth could have succeeded in voluntarily throwing the Ring into the Fire.

But he came closer than probably anyone else would have.

So he deserved every bit of approbation he got – but I doubt he ever believed that he did.

Nevertheless, I am fully with you in why his failure/success hurts so much. Because it destroyed him (and that destruction makes for a text which can be read in so many ways).

pilgrimsoul @38 and Elaine Thom @39, I certainly didn’t mean to imply that Frodo kept his failure to himself, at least not in the long run.

I’m inclined to think he was too exhausted, too devastated, to have told anyone much of anything by the time the ritual praise, happened though (not that it would have matter; he was going to be a Hero no matter what he had done.

The loss of Frodo’s finger makes me think of a bit from C.S. Lewis, in The Great Divorce:

“The attempt is based on the disastrous belief that reality never presents us with an absolutely unavoidable ‘either-or’… that mere adjustment or refinement will somehow turn evil into good without our being called on for a final and total rejection of anything we should like to retain. This belief I take to be a disastrous error. You cannot take all luggage with you on all journeys; on one journey even your right hand and your right eye may be among the things you have to leave behind.” (p. 2 in my edition)

I have always wanted to know whether he is referring to anything specific or whether it is his own concept, and have never been able to track the reference any farther. The Great Divorce came out in 1945, though I don’t know whether Tolkien read it; at any rate I find this passage very interesting with reference to LOTR, given that Frodo does the opposite of rejecting and the evil is removed from him anyway.

@Rush-That-Speaks — I believe that Lewis is making a fairly explicit reference there to Matthew 5:29-30.

My idiosyncratic take on the Lay of Frodo, etc., is that it had more to do with the importance of stories — stories in some way being “real-er than real” — similar to the line that Peter Jackson gives Sam in the movie, about “the great stories, the ones that really matter.”

In that sense, it wasn’t the battered Frodo, sitting there in his rags, who was being honored at all. It was the Mythic Frodo, the Story-Hero, if you will the Frodo in the Realm of the Ideas / Logos / Story, of whom the flesh-and-blood Frodo was a Platonic shadow.

And that weary and heartsore Frodo perhaps needed that Story Frodo at that moment more than anyone.

Lemnoc @@@@@ 16,

I don’t think you can call it a “happy ending” in any sense. I can’t help but wonder if part of Tolkien’s point here was (again) based on his WW1 experience that the dead aren’t the only losses, and that some who come home “alive” and “well” are just as dead in their own way.

Frodo gave the ultimate sacrifice; it just took everyone (including Frodo) a while to figure that out. Arwen knew first, perhaps, 2 chapters from now.

Not only am I disappointed that Aragorn and Gandalf weren’t fighting, but I’m disappointed not to see the Eagles fight the Nazgûl.

Gwaihir says, “The North Wind blows, but we shall outfly it.” First, there have probably been enough comparisons of speed to the wind. Second, I should hope he’d have an airspeed above zero!

Sam isn’t depressed on Mount Doom, but he, like Frodo, foregoes the opportunity to console himself by pointing out that their quest did succeed and the world is saved.

An odd thing about praise is that everybody talks about it but nobody does it. Aside from the lay that we never hear, and Gandalf’s comment that Frodo’s orc rags are the most honorable of garments, nobody every tells Frodo he did a good job. Aragorn doesn’t say that based on his moments of temptation, he can only imagine how Frodo held out so bravely, weakened by hunger and thirst. No tall warrior of Minas Tirith admits that he might have run from Shelob, once the story of Sam and Shelob comes out. (Nobody praised Merry either, though Gandalf did tell him his name was in honor.)

ed-rex @@@@@ #22: So I agree with you that Tolkien may have been uncomfortable with praise and didn’t totally overcome his (English?) reticence about it.

Speaking of which, whatever the importance of Frodo’s throwing away his weapons was, Gandalf appears to think the Done Thing is more important.

I’m not embarrassed by this chapter as Kate and others are (except when Sam and Frodo sit in the same chair, like five-year-olds when company comes over), but it doesn’t move me the way it moves still others.

I’d better save this before I accidentally delete it the way I did my first version.

@@@@@Rush-That-Speaks: Let’s reread Engine Summer!

I’m a bit surprised that Frodo and Sam didn’t get to see Merry and Pippin earlier. I’d have thought they’d be a high priority. Like Kate, I enjoyed, “We are knights of the City and of the Mark, as I hope you observe.” It might be my favorite moment in the chapter.

In Rivendell, back when Frodo was the main POV character, there was a gap while he was unconscious and Sam was busy. Now that Sam’s been the main POV character for a while, the gap ends when he wakes, though Frodo’s already been awake. (We’re going to go back to Frodo, though.) Another example of Sam’s climb in status is that although he still says “Mr. Merry” and “Mr. Pippin”, he can “make” them stand back to back with him and Frodo, which I can’t see him doing before.

@@@@@NancyLebovitz: Good point about the overwhelming wave. And I just figured out what your post on the minor incident reminded me of: In Perelandra, Ransome didn’t even notice when he got the one wound in his fight that turned out to be permanent.

hapax @@@@@ #49: I was interested in your comment about the value to Frodo of the Story. Maybe all this was Aragorn’s and Gandalf’s best attempt to treat Sam’s and Frodo’s PTSD (along with medicating them with kingsfoil). It would probably be anachronistic to suggest that Frodo would feel better on anniversaries if someone had talked about his failure at the Sammath Naur and helped him take a rational attitude toward it.

Tolkien not only read The Great Divorce, he had heard Lewis read chapters out loud while it was still a work in progress. In Letter #69, Tolkien says:

Who Goes Home? was the working title, of course.

alfoss1540@19–

Yep, when Star Wars cuts to R2-D2 at the ceremony, I tear up. (The Millenium Falcon return also does; check out Jo Walton’s thread today on tear-worthy SF.)

firkin @@@@@ #10, I concur with others that the amputations echo themes other than Christianity, and also are a useful way of demonstrating permanent effects of hard times without actually killing your hero.

Dr. Thanatos @@@@@ #11, Sam didn’t get his own song either . . .

Lemnoc @@@@@ #16, would you feel differently about the balance of the outcome of the ending if Pippin or Merry had died? Because I do think that it’s improbable for all of the hobbits to have survived, but for me one death and then Frodo’s realization that he can’t enjoy victory might strike a more realistic balance.

alfoss1540 @@@@@ #20, nice, though please lower-case that “merry” throughout lest the very wrong impression be given . . .

SoonLee @@@@@ #21, fabulous link. And yes, you’re right that celebrations of heroes are mostly not about what the heroes would want, but the way that it’s portrayed as so wonderful for Sam specifically can’t help but make me think of what Frodo thinks.

ed-rex @@@@@ #22, 46–Frodo only woke up earlier that day, so I’m thinking most of events were from Gandalf seeing things like he did in Rivendell, to give the ministrel _time_ to compose a big long lay about events.

SoonLee @@@@@ #29, re: chipped nail: *groan*

DemetriosX @@@@@ #37, re: experience of the armistice–interesting. My emotional reaction to WWI is permanently shaped by _Rilla of Ingleside_ (of all things) and I remember well the kind of stunned incredulous joy the characters had when they heard that peace was on the way.

hapax @@@@@ #49, that is a very interesting point. It wouldn’t work that way for me, and I have a hard time imagining it would work for Frodo, but maybe.

Jerry Friedman @@@@@ #51-52, huh. Do we get a lot of praise elsewhere? Gandalf tells Pippin he did his best after he meets Denethor. Umm . . . I’m sure Frodo must tell Sam he’s done well at various points.

And yes, why didn’t Frodo and Sam ask after Merry and Pippin earlier in the chapter?

(I think I said something earlier about wishing Middle-earth had better psychological treatment . . . )

And just in case it’s in doubt: people who like this chapter, I’m happy for, and a little jealous of, you, seriously!

Re Orcs

-I had never thought of it before, but them killing themselves does seem a bit odd. Although maybe getting

out from under Sauron’s spells is a bit like postpartum depression. You get a little crazy for a bit when the hormones go away.

-I am less surprised that they run away, however. Why not? When Shagrat and Gorbag (why does Tolkien not tell us about orc names in appendix Y or whatever it is. I would love to read that) were discussing the perfect life it was just a bunch of lads and loot handy. There is no loot be won here, and Aragorn is scary. The Men may prefer death before dishonor, or may just be really pissed that those white-skined goody-goodies are winning after all, but I doubt the orcs care.

-I had not realized that orcs are not mentioned as a problem after this, but then I’m not sure they would be organized enough to earn a listing in the short version of the Mighty Deeds of the King. Even before this orcs were mostly a threat to Gondor when led by someone, otherwise they were just orc-bands in the hills. You needed Corsairs or Wainriders to make a threat (I could be remembering this wrong.)

-One thing that makes me happy is that I just realized that Shagrat calls for a bunch of “lads” in his ideal society. of looters If one assumes that loot includes beer (it did for Bilbo’s trolls) then all that is missing is babes. (You really do need them one way or another. It’s always loot and rapine,

not just looting) We never get a description of orcish ideas about sex. Thank the Valar for Tolkien’s prudishness, even if figuring out if orcs get married or whatever would make for an interesting investigation of what evil is for him.

kate@55:

Even though the hobbits have only been separated for a few weeks what Frodo and Sam have gone through make it a lifetime. On top of their ordeals making it hard to remember their friends and the good things in life, their world was severely circumscribed into just the two of them and sometimes Gollum.

This may reflect Tolkien’s war experience again, when on coming home, he found himself thinking more about the men in his unit (on whom his life had depended and whose lives depended on him) than his friends and family at home. Heinlein deals with this a bit, too, in some of his books. Space Cadet comes to mind and, I think, Tunnel in the Sky, where the protagonists have problems when they go home, because their minds are still focused on their comrades-in-arms.

Kate @@@@@ #55: My favorite reference for the joy the soldiers felt at the end of WWI is Siegfried Sassoon’s poem http://net.lib.byu.edu/english/wwi/over/sang.html

]”Everyone Sang”.[/url]

On praise, back in “The Tower of Cirith Ungol”, Frodo said, “Sam, you’re a marvel!” But “Then quickly and strangely his tone changed.” I haven’t looked for other examples.

Aragorn said Éowyn’s “deeds have set her among the queens of great renown,” but we don’t hear that anyone has praised her while she was conscious, as I recall. (Faramir will, but he has another reason.)

But what I find particularly strange is saying “Praise them!” instead of “Well done!” or something specific.

alfoss1540 @@@@@ #20: Speaking of praise, that was sick :-)

Rabscuttle @@@@@ #56: I always assumed that orcs depended on Morgoth or Sauron for their life, though they may not have realized it, and became extinct at this point.

Not half-orcs, though. But if it weren’t for people taking the idea of half-orcs seriously, the reader could imagine orcs reproduce asexually. I think you’re absolutely right to ascribe this to Tolkien’s prudishness, at least in this book, and to point out that it’s conspicuously missing from Gorbag’s little utopian fantasy in “The Choices of Master Samwise”. Another spot is when Uglúk refers to Saruman as “the Hand that gives us man’s-flesh to eat”. Considering that Saruman seems to be cross-breeding humans and orcs, Uglúk could mention giving orcs woman’s-flesh too, and Tolkien could have written it without breaking taboos, the way he informed us of Wormtongue’s desire.

DemetriosX @@@@@ #57: That’s a reason that hadn’t occurred to me for Frodo’s and Sam’s not asking about Merry and Pippin immediately, though they were their comrades in arms till a few weeks earlier. But it doesn’t explain why M. and P. don’t want to be with F. and S., or why Gandalf wouldn’t think it was a good idea.

Hmm…eagles coming to the rescue…air forces…

An echo of the Tommies’ feelings at U.S. support in WWs I & II?

(At least it wasn’t bears…or lions & unicorns…)

Tolkien does say somewhere in his Letters that Faramir had to clean out residual Orcs along with human outlaws in postwar Ithilien; some must have survived for a while!

Elaine Thom @39: To have him survive, willing to pay the ultimate price, triumphant, and

then realize he’s wounded and will never really heal, is one of the

elements that makes it a lasting work.

About 25 years ago, my friend was diagnosed with terminal cancer. All treatments had failed, and he had resigned himself to death within a few weeks or months at most. And then he started to get better. Not only did he start to get better, but he got betterer and betterer, to the point where an inoperable cancer became operable and was removed. He lived for a further 13 years and died very suddenly after a short and completely unrelated illness.

He put his remission down to a miracle, and for the rest of his life he was a very different person: more thoughtful, more light-hearted and, dare I say it, basically better. Yet on several occasions he mentioned his disquiet about his recovery and “why” he had been spared. He observed that, once you have finalised your worldly affairs, made your peace with God and cancelled the newspaper, to suddenly find that you’re making a full recovery is not unalloyed good news. What do you do with your life now?

I think we see echoes of this in Frodo’s subsequent behaviour. He expected death, and death did not come. For the remainder of the book, he’s never entirely “there”. In the end, his departure from Middle Earth comes as a relief to him. He didn’t die in the fires of Orodruin, but part of him did.

(still) Steve Morrison @@@@@ #60: I guess that settles what happened to the Orcs, though I think you can read the text either way.

Your mailbox is full @@@@@ #61: That’s a very interesting point, and maybe relevant to Frodo (though not Sam), but I think it’s going too far to say Frodo isn’t entirely “there” in “The Scouring of the Shire”.

I think of Frodo’s condition during this chapter as if he’s been somewhat deafened by an overwhelming amount of sound. He is a bit removed from everyone around him. He can see and hear but everything is dimmer and further away than normal. It wouldn’t be hard to sit through bards in such a state.

I felt a tremendous amount of relief and joy at this chapter when I was eleven. Frodo and Sam were among enemies in the dark place of peril and now they are safe with friends.

ed-rex @23

I think Lucas modeled the awards ceremony almost shot for shot with a famous Nazi propaganda film.

ed-rex @23

The film was called ‘Triumph of the Will’ from 1935.

@NickS, 64 and 65, the thing is, I knew that and I have known it for a very long time. Worse, I saw Star Wars before I read Tolkien. I can only explain the lapse as a wish that Lucas was cribbing from Tolkien rather than Reiffenstahl (?). If that explains anything at all.

@29: in Tolkien’s legendarium, there was to be a final battle (I guess that would be in the Fourth Age? Much later?) — the Dagor Dagorath — when Morgoth would escape from the void and cast the world into darkness, but the Valar and others will battle with him, and Turin Turambar son of Hurin himself would destroy Morgoth with his Black Sword Gurthang, and thus avenge Men and all free peoples, and then Eru Iluvatar will begin a Second Music of the Ainur and the world would be remade. So basically evil would be dealt its final death blow for in the biggest, baddest battle of all.

Don’t try anything or Sam will klll, Sam will klll, Sam will klll,

Frodo & Sam had 2 weeks treatment before they recovered. I don’t know anything about elven medicine .How about medieval medicine? First treatment for dehydration: if too weak to swallow, could receive fluid per rectum with a sheep’s horn. Then bathing in clean warm water infused with comfrey – this truly speeds healing of cuts & bruises. Then gradual nourishment with broth, soups & purees

Elrond in Rivendell kept Frodo anaesthetised while removing the .fragment of Morgul blade. I gather Aragorn had to cross a border to bring them back [ ? like Ged in Earthsea] but I don’t see the need for 2 weeks’ coma. They would need a swallowing reflex & preferably chewing. I guess the sons of Elrond would cover while Aragorn was involved with military duties. No women camp followers mentioned.

I guess this is part of leaving out messy stuff like burial of casualties after battle. Good people can get killed, but apart from Frodo, no amputations, no sepsis, no long term head injuries.